6. Chapter 6: Confidence Intervals and Significance Tests#

Last chapter, we learned that the sampling distribution of the sample mean \(\bar{X}\) is approximately \(\mathcal{N}\left(\mu, \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\right)\) under mild conditions, thanks to the Central Limit Theorem (CLT). The mean of this sampling distribution is \(\mu\), making the sample mean \(\bar{X}\) an excellent candidate for a point estimator of the population mean \(\mu\).[1]

However, in reality, we typically only observe one sample, and the sample mean \(\bar{X}\) itself is random. Using our knowledge of the sampling distribution, we want to assess how far the observed \(\bar{x}\) is from the population mean \(\mu\), or equivalently, how far the population mean \(\mu\) might be from our observed \(\bar{x}\). This motivates the need to address uncertainty in our estimates of population parameters.

One effective way to quantify this uncertainty is by constructing a confidence interval, which provides an interval estimate for the population mean. A typical confidence interval for the population mean is expressed as:

and we interpret it as:

“Given the data, we are 95% confident that the true mean \(\mu\) lies within this range.”

The Margin of Error is a calculable value that reflects the range within which the true population mean \(\mu\) is likely to lie, based on the observed sample. An important clarification involves two equivalent perspectives when interpreting the range:

We say \(\mu\) lies within the interval \((\bar{x} - \text{Margin of Error}, \bar{x} + \text{Margin of Error})\), or

We equivalently say that \(\bar{x}\) lies within the interval \((\mu - \text{Margin of Error}, \mu + \text{Margin of Error})\). The second perspective arises from our understanding of the sampling distribution and the variability inherent in the sample mean.

Proof. The two statements are logically equivalent.

Claim: The two statements \((\bar{x} - \text{margin} < \mu < \bar{x} + \text{margin}) \text{ and } (\mu - \text{margin} < \bar{x} < \mu + \text{margin})\) are logically equivalent.

Hence the intervals \(\bar{x} \pm \text{margin}\) around \(\mu\) and \(\mu \pm \text{margin}\) around \(\bar{x}\) represent the same set of inequalities.

The first perspective focuses on \(\mu\) (the true population parameter) as the unknown, while the second perspective focuses on \(\bar{x}\) (the sample statistic) as a random variable. Recognizing that these two perspectives are equivalent, we can construct the confidence interval in the first perspective using the knowledge of the sampling distribution from the second perspective. Since we understand the distribution of the sampling statistic, we can make probability claims about the range within which the random variable \(\bar{x}\) would fall if we repeatedly sampled from the population-this range forms the confidence interval.

The probability associated with this range is called the confidence level (e.g., 95%). I will discuss the interpretation of this level in detail in the next section.

For now, I want to briefly introduce a new concept: the Pivot or Pivotal Quantity.

A pivot, such as \(Z = \frac{\bar{X} - \mu}{\sigma / \sqrt{n}}\), is a function of the sample and parameters that has a distribution independent of the unknown parameter. Its distribution remains invariant regardless of the value of \(\mu\). This property allows us to connect the sample statistic and the population parameter with probability statements, as the distribution of the pivot is known even if the parameter values are not.

Designing or identifying appropriate pivots is a non-trivial task, but they are essential tools for statistical inference. In this course, we will encounter several examples of pivotal quantities, each playing a crucial role in hypothesis testing and confidence interval construction.

6.1. Estimating with Confidence#

Let’s begin with the simplest case: we are working with the sample mean \(\bar{x}\), and our goal is to construct a confidence interval for the population mean \(\mu\). Additionally, we assume that the population standard deviation \(\sigma\) is known-a scenario that is rarely true in practice.

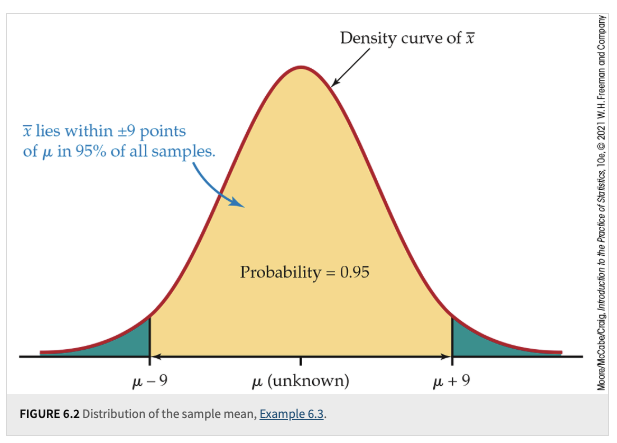

Using our knowledge of the sampling distribution of sample means, we know that \(\bar{X}\) is approximately distributed as \(\mathcal{N}\left(\mu, \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\right)\) under the Central Limit Theorem. Leveraging our understanding of probability and the properties of the normal distribution (such as the 68-95-99.7 rule), we can determine the probability of \(\bar{x}\) falling within specific intervals under the normal density curve.

For example, the 68-95-99.7 rule tells us that 95% of the area under the normal curve lies within 2 standard deviations from the mean. Therefore, if we repeatedly took samples and calculated \(\bar{x}\) for each sample, approximately 95% of these \(\bar{x}\) values would lie within the interval:

This illustrates the second perspective, where we view \(\bar{x}\) as a random variable distributed around the true mean \(\mu\). This perspective allows us to build confidence intervals using probability derived from the sampling distribution.

Fig. 6.1 Example 6.3#

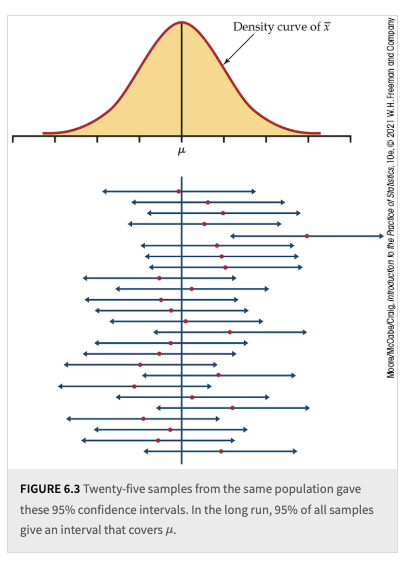

Now, let’s shift to the first perspective, where our focus is on the population parameter \(\mu\). Given each sample mean \(\bar{x}\), we can construct a confidence interval for \(\mu\) as follows:

We call these 95% confidence intervals for \(\mu\). Since \(\bar{x}\) is a random variable, the confidence interval itself is also random-its endpoints change depending on the sample we obtain.

Interpretation of Confidence Intervals:

In the long run, if we repeatedly take samples and construct confidence intervals using the formula above, approximately 95% of these intervals will contain the true population mean \(\mu\).

However, for any specific confidence interval derived from one sample, we do not know whether that particular interval actually contains \(\mu\).

More importantly, we cannot assign a probability to whether this specific interval covers \(\mu\) or not.

This last point is where many people misinterpret confidence levels-thinking that an individual confidence interval has a 95% probability of containing \(\mu\), when in reality, the probability statement applies to the process, not a single interval.

Fig. 6.2 Example 6.3, 25 Samples#

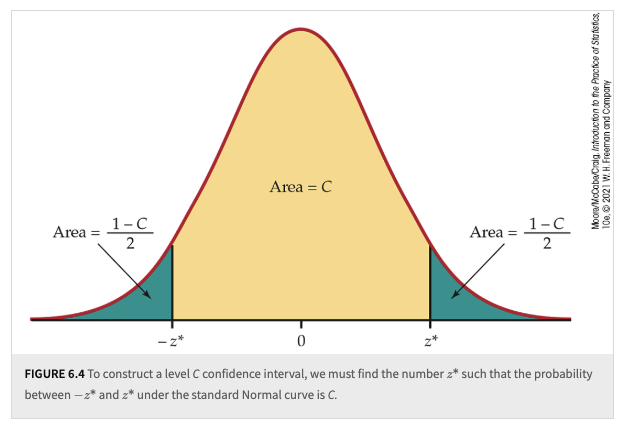

Of course, we are not limited to a 95% confidence level-we can choose any other confidence level. However, adjusting the confidence level requires modifying our interval. Instead of using:

we replace the value 2 with a more general critical value, denoted as \(z^*\).

Key Observations:

If we increase the confidence level, the value of \(z^*\) becomes larger, resulting in a wider confidence interval.

If the sample size increases, the confidence interval becomes narrower, reflecting increased precision in our estimate.

Determining the Required Sample Size:

If we want to achieve a desired margin of error, denoted as \(m\), while keeping the confidence level fixed, we can solve for the necessary sample size \(n\). Rearranging the margin of error formula, we obtain:

\[n = \left(\frac{z^* \sigma}{m}\right)^2.\]This equation helps us determine the required sample size to achieve a specified margin of error for a given confidence level.

Definition 6.1 (Confidence Interval for a Population Mean)

Choose an SRS of size \(n\) from a population having unknown mean \(\mu\) and known standard deviation \(\sigma\). The level \(C\) margin of error of \(\bar{x}\) is:

Here, \(z^*\) is the value on the standard Normal curve with area \(C\) between the points \(-z^*\) and \(z^*\). The level \(C\) confidence interval for \(\mu\) is:

The confidence level of this interval is exactly \(C\) when the population distribution is Normal and is approximately \(C\) when \(n\) is large in other cases

Fig. 6.3 \(C\) level CI#

6.2. Tests of Significance#

The second classical statistical method for using sample information to make inferences about the population-generalization-is the hypothesis test. This method is also closely related to the pivotal quantity mentioned earlier. However, in this context, we refer to it as a pivot statistic, test statistic, or observed pivot.

Logic of Hypothesis Testing:

The reasoning behind hypothesis testing can feel counterintuitive because we begin by assuming an explanation for how the dataset is generated. In this framework, we act as if we are the Oracle, knowing the true value of the parameter of interest under the null hypothesis, denoted as \(H_0\).

We assume \(H_0\), which specifies a fixed value for the parameter.

We calculate a test statistic using sample data and the assumed parameter value from \(H_0\).

We evaluate whether the observed test statistic provides sufficient evidence to reject \(H_0\).

A common choice for \(H_0\) represents a “nothing interesting is happening” scenario/a “business as usual” hypothesis, or a hypothesis which something we seek to refute using sample data.

Scenario 1: Suppose we are studying the heights of Purdue students and it is generally believed that the average height of Purdue students has historically been 70 inches. The null hypothesis here would reflect the “business as usual” assumption:

Null hypothesis (\(H_0\)): The average height of Purdue students is 70 inches (\(\mu_0 = 70\)).

Scenario 2: A researcher claims that Purdue’s new student population has an average height of at least 72 inches, suggesting a significant increase in height due to some unknown factor (e.g., recruitment policies). Here, the null hypothesis reflects the claim that the researcher tries to refute using data:

Null hypothesis (\(H_0\)): The average height of Purdue students is at least 72 inches (\(\mu_0 = 72\)).

Once we have formed our Null hypothesis, we can form our alternative hypothesis which assert that a mechanism other than the null hypothesis generated the datasets.

Definition 6.2 (Null Hypothesis)

The statement being tested in a test of significance is called the null hypothesis. The test of significance is designed to assess the strength of the evidence against the null hypothesis. Usually, the null hypothesis is a statement of “no effect” or “no difference.”

We still rely on our knowledge of sampling distributions and pivotal quantities. Here, we substitute the hypothesized parameter value \(\mu_0\) from \(H_0\) (which we assume to be known) into the test statistic formula to calculate the test statistic.

By conditioning on the assumption that the null hypothesis is true, meaning that \(\mu_0\) is the actual population mean, we can determine the probability of obtaining a test statistic as extreme or more extreme than the observed value. This probability is known as the p-value.

Interpreting the p-value:

The p-value represents the probability of observing data as extreme as (or more extreme than) the sample data, given that \(H_0\) is true.

If this probability is small (i.e., the p-value is less than a preset significance level \(\alpha\)), we reject the null hypothesis \(H_0\).

A small p-value suggests evidence against \(H_0\), indicating that the observed data are unlikely under the null hypothesis.

“The p-value is the probability of observing a test statistic as extreme as, or more extreme than, the one computed from your sample data, assuming the null hypothesis is true.”

The p-value is the probability of observing a test statistic as extreme as, or more extreme than, the one computed from your sample data, assuming the null hypothesis is true.

p-value \(\neq\) Probability that \(H_0\) is true

The p-value is conditional on \(H_0\) being true; it does not tell us the probability of \(H_0\) itself.

p-value \(\neq\) Strength of the alternative hypothesis (\(H_a\))

A small p-value suggests \(H_0\) is unlikely, but it doesn’t measure how true \(H_a\) is.

“Failing to reject \(H_0\)” \(\neq\) Proving \(H_0\)

A high p-value means the data are consistent with \(H_0\), but it doesn’t prove \(H_0\) is correct.

If the p-value is as small or smaller than \(\alpha\), we say that the data are statistically significant at level \(\alpha\).

The formula for the test statistic is as follows:

Recall from Chapter 5 that the standard deviation of the sample mean, \(\bar{x}\), is given by: \(\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\)

Therefore, the test statistic becomes:

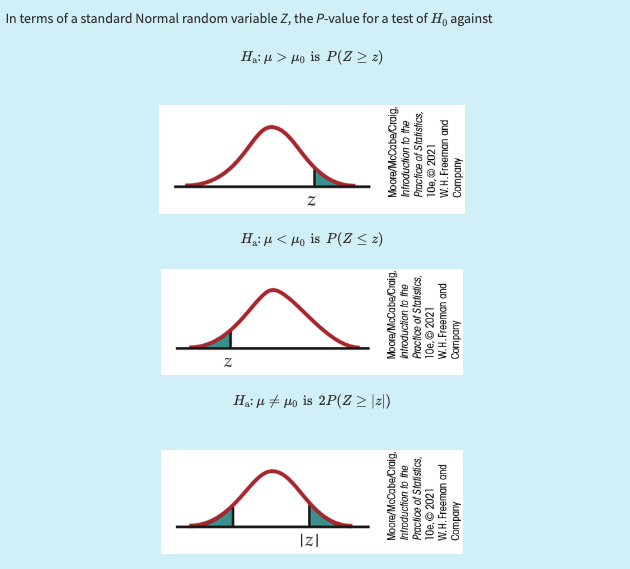

Then, we can use a z-table to find the probability statements like, \(\mathbb{P}(Z \geq z)\) or \(\mathbb{P}(Z \leq z)\).

A level \(\alpha\) two-sided significance test rejects a hypothesis \(H_0: \mu = \mu_0\) exactly when the value \(\mu_0\) falls outside a level \(1 - \alpha\) confidence interval for \(\mu\).

P-values provide more information than simple reject/not-reject decisions:

P-values are more informative than the reject-or-not result of a level \(\alpha\) test. Beware of placing too much weight on traditional values of \(\alpha\), such as \(\alpha = 0.05\).

Statistical significance does not imply practical significance:

Very small effects can be highly significant (small \(P\)), especially when a test is based on a large sample. A statistically significant effect need not have practical significance.

Always plot the data to display the effect you are seeking and use confidence intervals to estimate the actual values of parameters.

Lack of significance does not mean the null hypothesis (\(H_0\)) is true:

Lack of significance does not imply that \(H_0\) is true, especially when the test has a low probability of detecting an effect (low power).

Significance tests are not always valid:

Faulty data collection, outliers in the data, and testing a hypothesis on the same data that suggested the hypothesis can invalidate a test.

Beware of multiple comparisons:

Many tests run at once will probably produce some significant results by chance alone, even if all the null hypotheses are true.

p-hacking, “If you torture the data long enough, it will confess to anything” (attributed to Ronald Coase) humorously critiques the misuse of statistical methods, such as p-hacking, where researchers manipulate data or analysis methods to find statistically significant results, often leading to misleading or invalid conclusions.

6.3. Inference as a Decision#

From the last section, we saw that after conducting a hypothesis test, we must make a binary decision based on the p-value:

Reject \(H_0\)

Fail to reject \(H_0\)

This type of binary decision-making also appears in many important real-life applications. For example, in the court system, a judge must decide whether to reject \(H_0\) (i.e., declare the suspect guilty) or fail to reject \(H_0\) (i.e., maintain the assumption of innocence) based on the available evidence.

The Possibility of Errors:

However, given our understanding of random sampling and sampling distributions, we recognize an inherent limitation in this statistical decision-making process. Even if we follow the hypothesis testing procedure correctly, there is always the possibility of making a wrong decision due to the randomness of the test statistic.

This means that the conclusion we draw from the statistical test might contradict the true state of the population. These discrepancies are known as statistical errors. For example:

Type I Error: Rejecting \(H_0\) when \(H_0\) is actually true.

In court terms: Convicting (finding guilty) someone who is actually innocent.

Due to sheer misfortune, Mother Nature provides you with a rare dataset that yields an unusually extreme test statistic.

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{Type I Error}) = \mathbb{P}(\text{rejecting } H_0 \text{ when } H_0 \text{ is true}) = \mathbb{P}(\text{rejecting } H_0 \mid H_0 \text{ true}) = \alpha\)

Type II Error: Failing to reject \(H_0\) when \(H_0\) is false.

In court terms: Acquitting (finding not guilty) someone who is actually guilty.

You are unlucky, and Mother Nature hands you a dataset that fails to reveal the real effect.

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{Type II Error}) = \mathbb{P}(\text{failing to reject } H_0 \text{ when } H_0 \text{ is false}) = \beta\), and \(1-\beta\) is called the power of the test.

To calculate the probability of a Type II error \(\beta\), we must specify the true value of the parameter under the alternative hypothesis. For instance, if our null hypothesis states \(\mu = \mu_0\), we must assume a particular value \(\mu = \mu_0 + \delta\) (for some \(\delta \neq 0\)) to compute \(\beta\).[2]

Finally, let’s consider a few remarks on the significance-test perspective and the decision-theory perspective for making inferences.

Note

1. Significance Tests (Fisher’s Perspective)

Focus: A single hypothesis \(H_0\) and a single probability (the p-value).

Goal: Assess the strength of evidence against \(H_0\).

Outcome:

If data are sufficiently against \(H_0\), reject \(H_0\).

Otherwise, conclude only that the evidence is insufficient to reject \(H_0\), not that \(H_0\) is actually true.

Power: Calculated to check how sensitive the test is to departures from \(H_0\).

Note

2. Decision Theory (Neyman-Pearson Perspective)

Focus: Two hypotheses, \(H_0\) and \(H_a\), with both Type I and Type II errors considered.

Decision Rule:

We choose one hypothesis based on the sample, and cannot simply abstain for lack of evidence.

We set \(\alpha\) to control Type I error and strive to minimize Type II error (maximize power).

Common Practice:

State \(H_0\) and \(H_a\).

Treat it as a decision problem, so Type I (\(\alpha\)) and Type II (\(\beta\)) errors matter.

Fix \(\alpha\) such that Type I error probability \(\leq \alpha\).

Among tests meeting the \(\alpha\) criterion, choose one that minimizes \(\beta\) (i.e., maximizes power).

Note

3. Historical Context

Neyman-Pearson framework (1920s-1930s) laid the foundation for decision-oriented hypothesis testing.

Fisher emphasized significance testing (p-values) over rigid decision rules.

The combined approach (“testing hypotheses”) is often seen in modern practice, balancing both:

Significance level (\(\alpha\)) to control Type I error.

Power (\(1-\beta\)) to reduce Type II error.