8. Chapter 12: One Way ANOVA#

In the previous chapter (Chapter 7), we learned the statistical procedure for comparing the means of two populations. Naturally, the next step is to consider what to do when there are more than two populations. For example, suppose we have three diets—Diet A, Diet B, and Diet C—administered to three independent groups drawn from different populations. The study then measures a response variable to determine whether at least one group mean differs statistically significantly from the others.

One approach is to use the two-sample procedure and perform multiple pairwise tests between the groups. In the case of three groups, this involves testing the following pairs: (Diet A, Diet B), (Diet B, Diet C), and (Diet A, Diet C). However, from our understanding of probability, each test carries a risk of a Type I error, and these errors can compound when multiple tests are conducted.

Example: The Risk of Multiple Two-Sample Tests

Consider a scenario where a researcher wants to compare the effectiveness of three different diets on weight loss. The three groups are:

Diet A

Diet B

Diet C

If the researcher were to perform independent two-sample t-tests, the following comparisons might be made:

Diet A vs. Diet B

Diet A vs. Diet C

Diet B vs. Diet C

Assume that in reality there is no true difference among the diets—any observed difference is due solely to random chance. Each individual t-test is typically conducted at a 5% significance level (i.e., \(\alpha = 0.05\)). This means that for each test, there is a 5% chance of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis (committing a Type I error).

However, when performing three separate tests, the probability of making at least one Type I error increases. The overall chance (also known as the familywise error rate) of a false positive can be approximated by:

For three tests at \(\alpha = 0.05\), this calculation becomes:

This means that even if there is no actual effect, there is roughly a 14% chance that at least one of the three comparisons will incorrectly appear significant purely by chance.

In contrast, a one-way ANOVA tests the null hypothesis that all group means are equal in a single overall test. This approach controls the Type I error rate at the desired level (e.g., 5%), rather than inflating it as with multiple two-sample tests. Therefore, when comparing three or more groups, one-way ANOVA provides a more reliable method of analysis.

Familywise Error Rate with 10 Diets

When comparing 10 diets, if we were to perform all possible pairwise two-sample tests, the number of comparisons would be:

Assuming each test is conducted at a 5% significance level (i.e., \(\alpha = 0.05\)) and the tests are independent, the probability of not making a Type I error in a single test is \(0.95\). For 45 tests, the probability of making no Type I errors is approximately:

Thus, the familywise error rate—the probability of making at least one Type I error across all tests—is:

Using a calculator, we find that:

so the familywise error rate is approximately:

This very high error rate illustrates why performing multiple two-sample tests without adjustment can lead to a substantial increase in the probability of obtaining false positives.

Knowing that performing multiple two-sample tests has an inherent drawback—namely, the compounded risk of Type I errors—we must pursue another approach to answer the question of whether at least one group mean differs from the others.

Recall from our study of sampling distributions that the sample mean, \(\bar{X}\), is a random variable whose variability is influenced by both the sample size \(n\) and the population standard deviation \(\sigma\). Even when drawing different samples from the same population, this inherent variability persists. In our scenario, we suspect that different groups are drawn from populations with different means (while sharing a common standard deviation). This introduces an extra layer of variability among the sample means.

To rigorously examine this question, we need a statistical procedure that formally studies the variation among multiple group means. This leads us to One-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance). One-way ANOVA is a method used to determine whether there are any statistically significant differences among the means of three or more independent groups. Hence, we will also form a pair of hypotheses and calculate a pivotal quantity (test statistic) to run a hypothesis test to determine whether we have evidence from our dataset to reject \(H_0\). The hypotheses are as follows:

The null hypothesis in one-way ANOVA is that all group means are equal:

The alternative hypothesis is that at least one group mean differs from the others.

The F-statistic is then compared against a critical value from the F-distribution (taking into account the degrees of freedom) to decide whether to reject the null hypothesis.

8.1. Inference for One-way ANOVA#

To concretely see how we decompose the variation of the data points in our group that leads to the variation in the sample mean (or group mean), it is best to start with a statistical model and make some assumptions. For example, consider the one-way ANOVA model:

The ANOVA model is expressed as:

where:

\(x_{ij}\) is the \(j\)th observation from the \(i\)th group,

\(\mu_i\) is the true (population) mean for group \(i\) — this is the systematic component (the “FIT”),

\(\epsilon_{ij}\) is the random error term — this represents the residual variation (the “RESIDUAL”).

One-way ANOVA relies on several assumptions:

Normality: The data within each group should be approximately normally distributed.

Homogeneity of Variance: The variances in different groups should be similar.

Independence: The observations must be independent of each other.

The \(\epsilon_{ij}\) are assumed to be from an \(\mathcal{N}(0, \sigma)\).

Why Assume a Common Standard Deviation?

Because sample means naturally vary due to sampling variability (which depends on both the sample size \(n\) and the underlying population standard deviation \(\sigma\)), one must assume that the populations all have the same standard deviation. This assumption, known as homogeneity of variance, is crucial. If each group had a different \(\sigma\), then the variation in the sample means would reflect not only differences in the true group means but also differences in the precision of those estimates, making it difficult to compare groups fairly.

Note

Rule for Examining Standard Deviations in ANOVA

If the largest sample standard deviation is less than twice the smallest sample standard deviation, we can use methods based on the assumption of equal standard deviations, and our results will still be approximately correct.

The idea behind ANOVA is that the total variation in the data can be divided into two main parts:

Between-Group Variation: Variation due to differences among the group means \(\mu_i\).

Within-Group Variation: Variation due to the random errors \(\epsilon_{ij}\) (i.e., variability within each group).

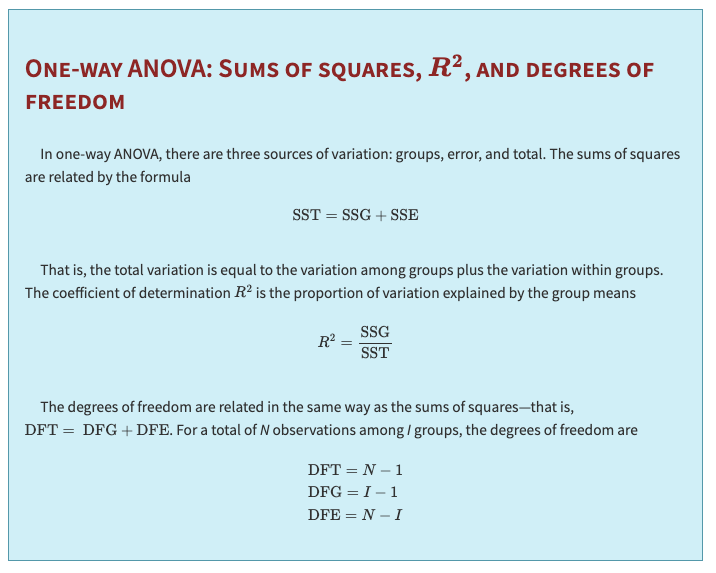

Mathematically, the total variation (often measured as the Total Sum of Squares, \(SS_{Total}\)) is given by:

where \(\bar{x}_{\cdot\cdot}\) is the overall (grand) mean of all observations.

This total variation is partitioned as follows:

In the textbook:

where:

Between-Group Sum of Squares (\(SS_{Between}\)):

\[ SS_{Between} = \sum_{i=1}^{I} n_i \left(\bar{x}_{i} - \bar{x}_{\cdot\cdot}\right)^2. \]This term measures how much the group means \(\bar{x}_{i}\) differ from the overall mean. It captures the systematic differences among the groups — the variation that can be attributed to the different treatments or conditions (reflected by the \(\mu_i\)’s).

Within-Group Sum of Squares (\(SS_{Within}\)):

\[ SS_{Within} = \sum_{i=1}^{I} \sum_{j=1}^{n_i} \left(x_{ij} - \bar{x}_{i}\right)^2. \]This term measures the variability of the observations around their respective group means, reflecting the random error \(\epsilon_{ij}\). The differences \(e_j = x_j - \bar{x}\) are the residuals and correspond to the \(\epsilon_j\) in the statistical model.

The total variation (or \(SS_{Total}\)) measures the overall spread of the individual data points around the grand mean. It tells us how much the data vary in total — a combination of:

Systematic differences among groups (if the \(\mu_i\)’s are very different, \(SS_{Between}\) is large), and

Random fluctuations within each group (if the \(\epsilon_{ij}\)’s are large, \(SS_{Within}\) is large).

These two sources of variation are independent.

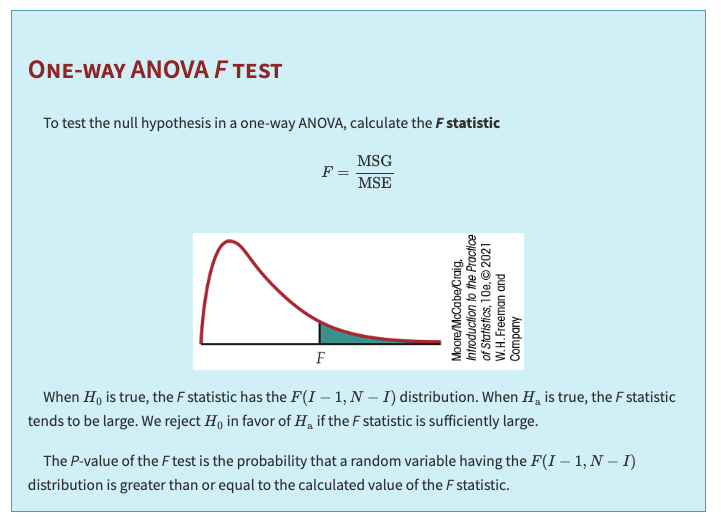

The ratio of the between-group variability to the within-group variability is computed to form the F-statistic:

A high F-value indicates that the variability between the groups is large compared to the variability within the groups. This suggests that at least one group mean is significantly different from the others.

An F-value close to 1 indicates that the between-group variability is similar to the within-group variability, suggesting no significant differences among the group means.

Mean Square Between (MSB):

\[ MSB = \frac{SS_{Between}}{I - 1}, \]Mean Square Within (MSW):

\[ MSW = \frac{SS_{Within}}{N - I}, \]where \(N\) is the total number of observations across all groups.

Under the Null Hypothesis: If the null hypothesis (that all group means are equal) is true, then the expected value of both MSB and MSW is the common error variance \( \sigma^2\). Thus, under \(H_0: \mathbb{E}\left(\frac{MSB}{MSW}\right) \approx 1\).

A significantly larger F value suggests that the group means differ more than would be expected by chance, prompting rejection of the null hypothesis.

8.2. Additional Materials from the Textbook#

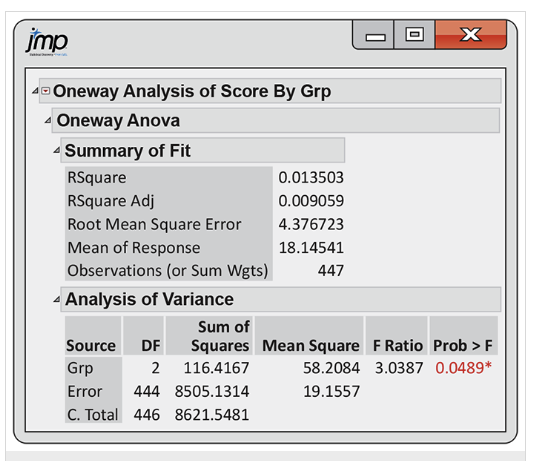

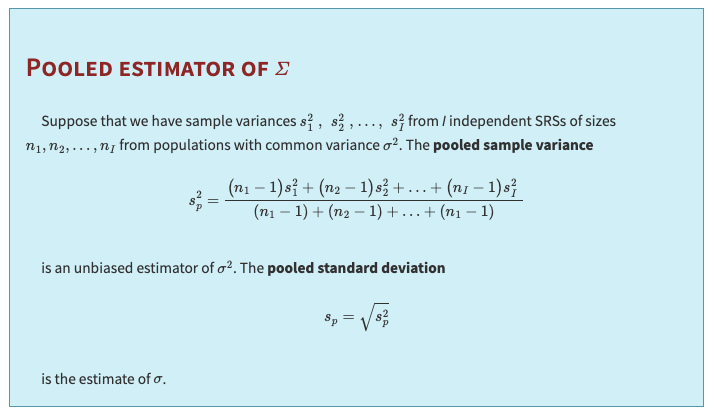

We can use the mean square for error to find \(s_p\), the pooled estimate of the parameter \(\sigma\) of our model. It is true in general that:

In other words, the mean square for error is an estimate of the within-group variance, \(\sigma^2\). The estimate of \(\sigma\) is, therefore, the square root of this quantity. So:

8.3. Supplementary Analyses Following One-Way ANOVA#

Once the overall F-test in a one-way ANOVA indicates that not all group means are equal, further analysis is needed to identify where the differences lie. Two common approaches are:

Multiple Comparisons Procedures

Contrasts

Below is an explanation of each method, why they are necessary, and their underlying logic.

Purpose

Identify Specific Differences:

While the ANOVA F-test tells you that at least one group mean is different, it does not specify which pairs of groups differ. Multiple comparisons procedures address this question by testing all (or selected) pairwise differences between group means.

Method

Pairwise Test Statistic:

For any two groups \(i\) and \(j\), the test statistic is computed as:\[ t_{ij} = \frac{\bar{x}_i - \bar{x}_j}{s_p \sqrt{\frac{1}{n_i} + \frac{1}{n_j}}}, \]where:

\(\bar{x}_i\) and \(\bar{x}_j\) are the sample means for groups \(i\) and \(j\),

\(n_i\) and \(n_j\) are the respective sample sizes,

\(s_p\) is the pooled standard deviation, assumed to estimate the common standard deviation across groups.

Decision Rule:

Compare \(|t_{ij}|\) with a critical value \(t^{**}\) (which is adjusted for multiple comparisons). If:\[ |t_{ij}| \geq t^{**}, \]then you conclude that the means \(\mu_i\) and \(\mu_j\) are significantly different.

Why It Is Needed

Control of Type I Error:

Testing many pairs increases the chance of false positives (declaring a difference when there is none). Multiple comparisons procedures use adjustments (like Bonferroni, Tukey’s HSD, etc.) to keep the overall Type I error rate at a desired level.Detailed Insights:

This method provides a complete picture of which specific groups differ from each other rather than just indicating a general difference among all groups.

Purpose

Test Specific Hypotheses:

Contrasts allow you to compare specific linear combinations of group means. This is especially useful when you have predefined hypotheses or when you want to compare groups in a structured way (e.g., comparing a treatment group to a control group).

Definition

Contrast Formula:

A contrast is defined as:\[ \psi = \sum a_i \mu_i, \]where the coefficients \(a_i\) are chosen such that \(\sum a_i = 0\). This condition ensures that the contrast represents a meaningful comparison (for instance, the difference between two weighted averages of group means).

Confidence Interval for a Contrast

Interval Construction:

A confidence interval for the contrast \(\psi\) is given by:\[ c \pm t^{*} SE_c, \]where:

\(c\) is the estimated contrast, \(c = \sum a_i \bar{x}_i\),

\(SE_c\) is the standard error of the contrast estimate, \(\text{SE}_c = s_p \sqrt{\sum \frac{a_i^2}{n_i}}\),

\(t^{*}\) is the critical value corresponding to the desired level of confidence,

DFE is associated with \(s_p\).

Hypothesis Test:

To test the null hypothesis \(H_0: \psi = 0\), we use the t-statistic:

\[ t = \frac{c}{\text{SE}_c} \]

Why It Is Needed

Focused Testing:

Contrasts allow you to test hypotheses that are more specific than “all means are equal.” For example, you might want to test whether the average of two treatment groups differs from a control group.Efficiency and Interpretability:

Instead of performing all possible pairwise comparisons, contrasts let you focus on comparisons that are of practical or theoretical interest. They are particularly powerful when the comparisons were planned before the data were observed (a priori contrasts).