7. Chapter 7: Inference for Means#

In the last chapter, we encountered the population parameter \(\sigma\) when calculating the margin of error for confidence intervals and computing the \(z\) test statistic for hypothesis testing. However, in practice, this \(\sigma\) is usually unknown.

Addressing the Unknown \(\sigma\):

In this chapter, we address this issue by making a more realistic assumption-that we do not know the value of \(\sigma\)-and explore how we can still conduct inference under two key settings:

Single-Sample Inference:

We have one sample and are interested in estimating the population mean \(\mu\).

This scenario mirrors what we saw in the previous chapter but now incorporates the unknown \(\sigma\).

Two-Sample Inference:

We have two independent samples, meaning we are dealing with two populations.

Our goal is to analyze the difference between the two population means, denoted as \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\).

Real-World Applications:

Many real-world problems fit into one of these two frameworks. Whether comparing before-and-after treatment effects, different experimental conditions, or population differences, these two settings provide a foundation for statistical inference when the population standard deviation \(\sigma\) is unknown.

7.1. Inference for the Mean of a Population#

If we do not know the population standard deviation \(\sigma\), we need to find an estimator to approximate it-just as we use the sample mean \(\bar{x}\) to estimate the population mean \(\mu\). Naturally, a reasonable choice is the sample standard deviation \(s\) as an estimator for the population standard deviation \(\sigma\).

Why Use \(s\) Instead of \(\sigma\)?

The sample standard deviation \(s\) is a good estimator of the population counterpart \(\sigma\).

We can show that \(s\) is an unbiased estimator of \(\sigma\), meaning its expected value equals \(\sigma\).

It is also a consistent estimator, meaning that as the sample size \(n\) increases, \(s\) gets closer to \(\sigma\).

Standard Error:

Since we do not know \(\sigma\), we also need to estimate the standard deviation of the sample mean, which is:

\[\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}.\]By replacing \(\sigma\) with its estimator \(s\), we obtain the standard error (SE) of our sample mean \(\bar{x}\):

\[\text{SE}_{\bar{x}} = \frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}.\]

The standard error quantifies the expected variability of the sample mean \(\bar{x}\) across different samples and plays a crucial role in confidence intervals and hypothesis testing.

1. Standard Error of the Sample Mean

We have a sample of size \(n\) from a normally distributed population with true mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\).

The sample mean \(\bar{x}\) has population standard deviation \(\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\).

Unknown \(\sigma\): If \(\sigma\) is not known, we estimate it with the sample standard deviation \(s\).

Therefore, the estimated standard deviation of \(\bar{x}\) is: \(\text{SE}_{\bar{x}} = \frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}\).

This quantity is called the standard error of the sample mean. It represents an estimate of how much \(\bar{x}\) varies from sample to sample.

2. \(z\) vs. \(t\) Statistics

When \(\sigma\) is known, we can use the one-sample \(z\) statistic:

\[z = \frac{\bar{x} - \mu}{\sigma / \sqrt{n}}\]which follows a standard normal distribution \(N(0,1)\).

However, when \(\sigma\) is not known and is replaced by \(s\), the statistic

\[t = \frac{\bar{x} - \mu}{s / \sqrt{n}}\]does not follow a standard normal distribution. Instead, it follows a \(t\)-distribution with \(n - 1\) degrees of freedom.

3. The \(t\)-Distribution

The \(t\)-distribution arises naturally when we estimate \(\sigma\) by \(s\).

It looks similar to the standard normal distribution but has thicker tails, especially for smaller sample sizes.

As \(n \rightarrow \infty\), the \(t\)-distribution converges to the standard normal.

In practice, the \(t\)-distribution allows us to perform inference on the mean when the population standard deviation \(\sigma\) is unknown, using \(s\) as an estimator.

Another setting where the one-sample t procedure is often used is in a matched-pairs design.

In a matched-pairs setup:

Each pair of observations is combined into a single difference value, yielding a single set of differences (one per pair).

Because these differences form one sample, the standard one-sample t test applies naturally to determine whether the average difference is zero.

The logic of a one-sample test remains the same-now we simply use within-pair differences rather than two separate sets of measurements.

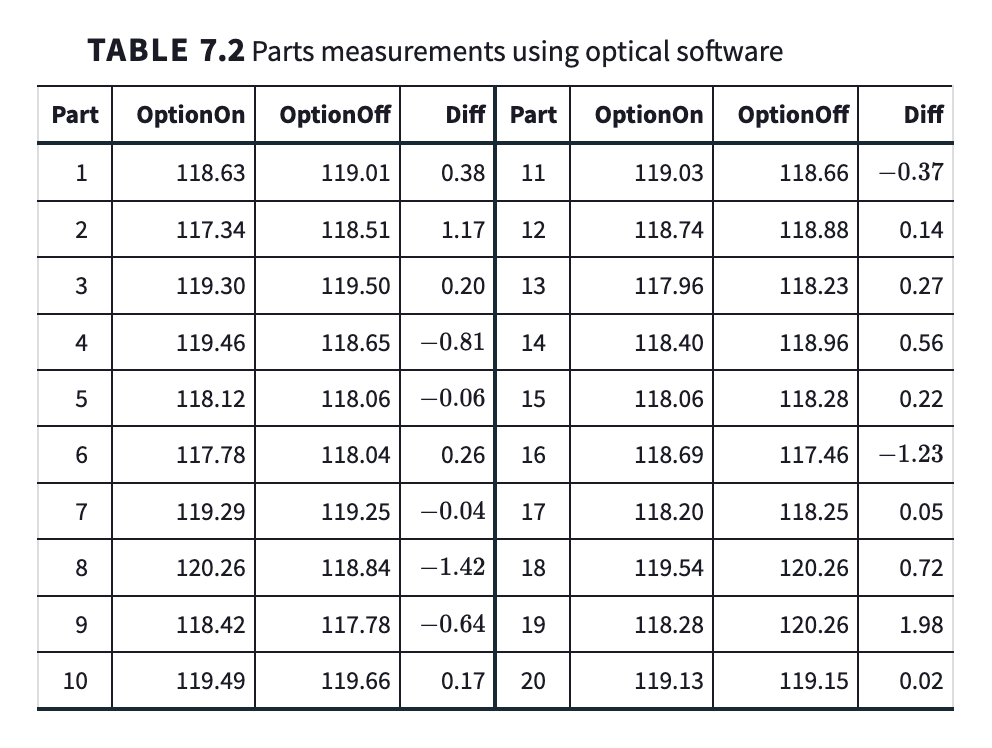

Scenario

Study Goal: Compare measurements of machine parts with and without a certain “option” enabled in the measuring software.

Data: Each part gives two measurements: Option On and Option Off. The difference \(d_i = (\text{On}_i - \text{Off}_i)\) is recorded for each part \(i\).

Sample Size: \(n = 51\) parts, so we have 51 paired differences \(d_1, d_2, \dots, d_{51}\).

Hypotheses

We test:

where \(\mu\) is the population mean of the difference in measurements (On minus Off).

Key Summary Statistics

\(\bar{d} = 0.0504\) (mean of the 51 differences)

\(s = 0.6943\) (sample standard deviation of the differences)

One-Sample \(t\) Statistic

This statistic follows a \(t\) distribution with \(n - 1 = 50\) degrees of freedom under \(H_0\).

Interpretation of Results

\(t = 0.52\), \(df = 50\).

The p-value (two-tailed) is greater than 0.50 (software reports approximately 0.6054).

Conclusion: There is no statistically significant evidence (\(p \approx 0.61\)) to conclude that the measuring option changes the average measurement.

When reporting results, it is common to say:

“The difference in measurements was not statistically significant (\(t = 0.52\), \(df = 50\), \(p = 0.61\)).”

Caution

A Lack of Statistical Significance \(\neq\) Proof of \(H_0\)

Failing to reject \(H_0\) does not mean we have proven \(H_0\) true; it often means that our study lacked sufficient evidence (or power) to show a difference.

If we could “prove” a null hypothesis by simply getting a non-significant result, we could always design weak experiments to achieve that outcome. Clearly, this is not sound science.

Here, we can shift our question slightly to:

“Is any difference too small to be important?”

By pre-specifying an acceptable difference \(\delta\), we conduct Equivalence Testing, which focuses on practical rather than purely statistical significance.

Why Standard Hypothesis Testing Is Not Enough:

A nonsignificant result in a standard hypothesis test does not necessarily mean two groups are equivalent.

Instead of simply failing to reject \(H_0\), we need to demonstrate with high confidence that the difference is within an agreed-upon small range.

The traditional “test vs. zero” framework does not establish equivalence-it only tests for a lack of sufficient evidence to reject \(H_0\).

Equivalence Testing Logic:

We define a small “practical” difference (threshold) \(\delta\) below which two means are deemed “close enough” to be considered equivalent.

We then ask if our data strongly indicate that any true difference cannot exceed \(\delta\) in magnitude.

Concretely, we build a confidence interval around our estimated difference.

If the entire CI fits within \((-\delta,\ \delta)\), we declare the two means “equivalent.”

If part of the CI lies outside \((-\delta,\ \delta)\), we lack evidence to conclude equivalence.

Motivation: Sometimes we want to show that two treatments or measurements are practically the same (i.e., any difference is too small to matter). A traditional hypothesis test merely tells us whether a difference is detectable, not whether it is small.

Approach:

Specify an equivalence range around the null value, say \(\mu_0 \pm \delta\). Any difference within \(\pm \delta\) is deemed “unimportant.”

Construct a confidence interval (CI) for the parameter of interest (often a mean difference).

If the entire CI lies inside \(\mu_0 \pm \delta\), we conclude equivalence. Otherwise, we lack evidence to declare them equivalent.

Key Point: Equivalence testing focuses on whether the true mean difference is small enough to be negligible, rather than simply testing if it differs from zero.

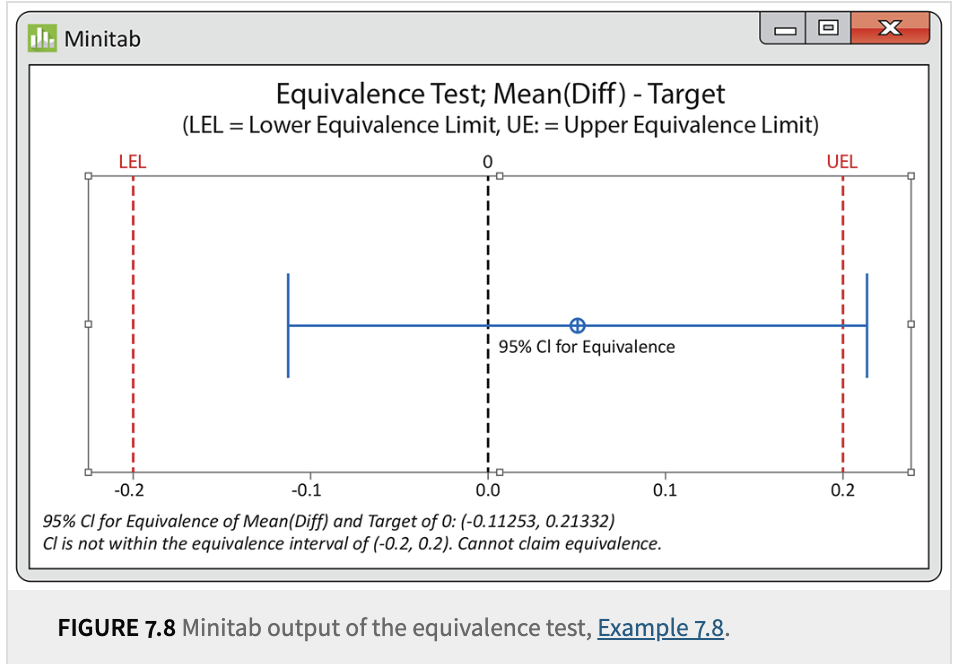

Scenario: Researchers consider a mean difference less than 0.20 micron “not important.”

Data: We have a sample of size \(n=51\), yielding \(\bar{x} = 0.0504\), and \(\text{SE}_{\bar{x}}=0.0972\).

90% CI: \(\bar{x} \pm t^*\,\text{SE}_{\bar{x}} = 0.0504 \pm (1.676)(0.0972) = (-0.112,\ 0.2133).\)

Since \(-0.112\) and \(0.2133\) are not fully contained in the “equivalence region” \([-0.20,\ 0.20]\), we cannot conclude equivalence at the 5% significance level. However, the mean difference is quite close to zero, so a larger sample might shrink the CI and yield a different conclusion.

Finally, we should discuss the robustness of t procedures and possible alternatives, especially when dealing with non-normal datasets.

Central Limit Theorem: For large samples, the distribution of the sample mean \(\bar{x}\) is approximately Normal, regardless of the population distribution.

Law of Large Numbers: As \(n\) grows, the sample standard deviation \(s\) becomes a reliable estimate of the true \(\sigma\), making t tests generally reliable even if the population is not perfectly Normal.

Sample size < 15: Use t procedures only if the data are reasonably close to Normal (no strong skew/outliers).

\(15 \le n < 40\): t procedures are typically fine unless you see strong skew or obvious outliers.

\(n \ge 40\): Even clearly skewed data can often be handled with t procedures.

These are rules of thumb for a single mean. The main concern is the presence of serious non-Normality or outliers in small samples.

3. Inference for Non-Normal Populations

When data are clearly non-Normal and \(n\) is not large enough to rely on the robustness of t tests, you have several options:

Use a Different Parametric Model

Some distributions (e.g., Poisson, exponential, etc.) have specialized methods if you can justify them.

Transform the Data

Skewness often improves under a transformation like \(\log(x)\).

Then apply the t procedure to the transformed values. Results are more accurate if the transformed data are closer to Normal.

Con: Interpreting confidence intervals in the original scale can be trickier.

Distribution-Free (Nonparametric) Procedures

These methods do not assume the population follows a Normal distribution.

Pro: More general.

Con: Often less powerful if the data were in fact close to Normal. Also, many such methods focus on the median rather than the mean.

7.2. Comparing Two Means#

Now, let’s shift our focus to two samples from two distinct populations. This scenario arises frequently in many real-world applications where we wish to compare two population means.

Fortunately, under mild conditions, the difference between the two sample means, \(\bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2\), is approximately normal. This allows us to extend the statistical procedures we learned for the one-sample case to this new two-sample setting.

Key Insights:

Just as in the one-sample case, we have both \(z\) statistics and \(t\) statistics for two-sample inference.

When the population standard deviations \(\sigma_1\) and \(\sigma_2\) are unknown and unequal, we use the standard two-sample \(t\) procedure.

However, if the two populations are assumed to have equal standard deviations (\(\sigma_1 = \sigma_2\)), we can pool the variance to obtain a more efficient procedure, known as the pooled two-sample \(t\) test.

By leveraging these different approaches, we can increase the accuracy and efficiency of our statistical inference when comparing two population means.

Note

Goals and Setup

Objective: Compare the means of a response variable in two different groups (populations).

Examples:

Comparing college students’ impressions from Wisconsin vs. Indiana.

Testing two different diets and measuring their impact on blood pressure.

Evaluating two incentive plans for debit card usage.

Key Conditions:

Each group is viewed as a distinct population.

We gather independent SRSs: one from each population.

The responses in group 1 are independent from those in group 2.

Notation

Population 1: Mean \(\mu_1\), Standard Deviation \(\sigma_1\), Sample Size \(n_1\), Sample Mean \(\bar{x}_1\), Sample SD \(s_1\).

Population 2: Mean \(\mu_2\), Standard Deviation \(\sigma_2\), Sample Size \(n_2\), Sample Mean \(\bar{x}_2\), Sample SD \(s_2\).

We often compare \(\mu_1\) and \(\mu_2\) by examining the difference \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\). In practice, we estimate this using \(\bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}_2\).

Two-Sample z Statistic (Population SDs Known)

If \(\sigma_1\) and \(\sigma_2\) are known:

The sampling distribution of \((\bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}_2)\) is Normal if both populations are Normal (or \(n_1, n_2\) are large enough by the Central Limit Theorem).

Mean of \((\bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}_2)\) is \((\mu_1 - \mu_2)\).

Variance of \((\bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}_2)\) is \(\frac{\sigma_1^2}{n_1} + \frac{\sigma_2^2}{n_2}\), assuming independence between the two samples.

The two-sample \(z\) statistic is:

When Population SDs Are Unknown: Two-Sample t Procedures

Typically, \(\sigma_1\) and \(\sigma_2\) are unknown in real-world settings.

We replace \(\sigma_1\) and \(\sigma_2\) by their sample estimates \(s_1\) and \(s_2\).

The resulting test or confidence interval is the two-sample t procedure.

As with the one-sample case, if the sample sizes are reasonably large (or if each group is approximately Normal), these t procedures are robust to moderate deviations from Normality.

We’ll derive the exact form of the two-sample t statistic, its degrees of freedom, and how to construct confidence intervals for \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\).

1. When Do We Use Two-Sample t Procedures?

Unknown \(\sigma_1\) and \(\sigma_2\): In real-world settings, population standard deviations are typically unknown.

Two Independent SRSs: We draw samples of sizes \(n_1\) and \(n_2\) from two populations with means \(\mu_1\) and \(\mu_2\), respectively.

Comparison of Means: We want to infer about \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\), either via hypothesis testing (e.g., \(H_0: \mu_1 = \mu_2\)) or a confidence interval (CI) for \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\).

By replacing \(\sigma_1\) and \(\sigma_2\) with their sample estimates (\(s_1\) and \(s_2\)), we obtain a t-based procedure instead of the (rarely used) two-sample \(z\) procedure.

2. The Two-Sample t Statistic

When \(\sigma_1\) and \(\sigma_2\) are unknown, the two-sample t statistic is

We typically test \(H_0: \mu_1 = \mu_2\) (or \(\mu_1 - \mu_2 = 0\)).

Under \(H_0\), \(\mu_1 - \mu_2 = 0\), so the statistic simplifies to

\[t \;=\; \frac{(\bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}_2)}{\sqrt{\frac{s_1^2}{n_1} + \frac{s_2^2}{n_2}}}.\]

Degrees of Freedom (\(k\)):

Exact distribution is complicated.

Software commonly uses the Satterthwaite approximation, which yields a t distribution with \(k\) degrees of freedom (not necessarily an integer).

No software? A conservative approximation is \(k = \min(n_1-1,\; n_2-1)\).

3. Two-Sample t Confidence Interval

A level \(C\) confidence interval for \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\) is:

where \(t^*\) is the critical value from the \(t(k)\) distribution cutting off an area of \(\frac{1 - C}{2}\) in each tail. The degrees of freedom \(k\) is approximated as above.

Assumptions/Conditions:

Independent samples: The two samples must be independent of each other.

Approximate Normality: For small samples, data from each population should be (roughly) Normal. For large \(n_1, n_2\), the t procedures are robust.

4. Summary

Two-sample \(z\) test: Rarely used because it requires known \(\sigma_1\) and \(\sigma_2\).

Two-sample t: Replaces unknown \(\sigma_1, \sigma_2\) with \(s_1, s_2\).

Hypothesis Tests: \(H_0: \mu_1 = \mu_2 \quad \text{vs.}\quad H_a: \mu_1 \neq \mu_2\) (or \(<\), \(>\)).

Confidence Intervals: Estimate \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\) with an interval.

Degrees of Freedom: Usually approximated by software.

These procedures allow you to draw inferences on the difference between two population means, even if you do not know the actual population standard deviations.

1. Hypothesis and Test Statistic

Hypotheses: Typically, we test

\[ H_0: \mu_1 - \mu_2 = \Delta_0 \quad\text{vs.}\quad H_a: \mu_1 - \mu_2 \neq \Delta_0 \quad(\text{or } <, >).\]A common case is \(\Delta_0 = 0\).

Two-Sample t Statistic:

\[t = \frac{(\bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}_2) - \Delta_0} {\sqrt{\frac{s_1^2}{n_1} + \frac{s_2^2}{n_2}}}.\]The degrees of freedom \(\,k\) are approximated (often by software using the Satterthwaite method).

p-Value: We use the t\((k)\) distribution to find the p-value or critical value for the test.

2. Robustness and Sample Size Guidelines

Just as with the one-sample t, these two-sample procedures are generally robust against moderate non-Normality.

Let \(n_1 + n_2 = n_{\text{total}}\).

If \(n_{\text{total}} < 15\), use t tests only if both samples look reasonably Normal (no major skew or outliers).

If \(15 \le n_{\text{total}} < 40\), the t test works well unless you see outliers or strong skewness.

If \(n_{\text{total}} \ge 40\), the t methods are quite robust, even for skewed data.

Equal Sample Sizes are especially recommended for better robustness and more accurate p-values.

3. Practical Tips

Choosing Labels: You can label whichever sample as “population 1” or “population 2.” It often makes the test statistic positive, avoiding confusion about negative values of \(t\).

Important: This is not the same as changing from a two-sided to one-sided test after seeing the data, which would be improper.

Small Samples: With very small \(n_1\) and \(n_2\), we have limited power, and confidence intervals become wide. Even so, if an effect is large, it can still be detected with small samples, but proceed with caution when distributions are unknown or heavily skewed.

1. Key Assumption: Equal Standard Deviations

We assume both populations have the same (but unknown) standard deviation \(\sigma\).

If true, we can combine (or pool) the two sample variances into a single estimate \(s_p^2\) to improve efficiency.

2. The Pooled Variance and t Statistic

Pooled Variance:

Degrees of Freedom: \(\;n_1 + n_2 - 2\).

Pooled Two-Sample t Statistic for testing \(H_0: \mu_1 - \mu_2 = \Delta_0\):

The corresponding confidence interval for \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\) uses the same \(s_p\) and t-distribution with \(n_1 + n_2 - 2\) degrees of freedom.

3. Advantages and Caveats

Advantages:

Higher degrees of freedom than the general (unequal-\(\sigma\)) two-sample t test, which may yield slightly narrower confidence intervals and smaller p-values if the equal-\(\sigma\) assumption holds true.

Risks:

The condition “\(\sigma_1 = \sigma_2\)” can be difficult to verify in practice.

If the population standard deviations differ substantially or the sample sizes are unbalanced, the pooled procedure can be misleading.

In modern practice, the unequal variance (unpooled) t approach is often safer-most software defaults to it (Satterthwaite approximation), unless you explicitly request pooling.

4. Why Use a Pooled Estimator for \(\sigma^2\)?

The formula assigns weights proportional to the degrees of freedom in each sample, emphasizing the larger sample if \(n_1 \neq n_2\).

Benefits:

Higher Degrees of Freedom: The pooled procedure uses \(n_1 + n_2 - 2\) df, often larger than the approximate df from the unequal-variance (Satterthwaite) method.

Efficiency: By combining variance estimates, we can get a more precise measure of the common \(\sigma\) when \(\sigma_1 = \sigma_2\) is truly valid.

Narrower Intervals: Tends to give slightly smaller standard errors (and thus narrower confidence intervals) if the equal-variance assumption holds.

7.3. Sample Size Calculations#

For all the statistical procdeures we have introduced so far, besides population stadndard devaition \(\sigma\) and sample standard deviation \(s\), we also see the sample size \(n\) in the formulas. In theory, this value is known to the researchers, but in practice, when we are planning a study, this is actually an important question, choosing the right number of sample size to make sure that the margin of error is less than a prespecified value \(m\) at a certain level of confidence. We know as sample size increase, our margin or error would decrease, however, increasing the sample size does not come free because we need to collect more data points. So that’ why we need to plan ahead to have large enough sample size to mmake sure we achieve \(m\).

We start with the formula for margin of error

For all the statistical procedures we have introduced so far, in addition to the population standard deviation \(\sigma\) and sample standard deviation \(s\), we also see the sample size \(n\) in the formulas.

In theory, the sample size \(n\) is known to researchers, but in practice, when planning a study, choosing the right sample size is an important decision. The goal is to ensure that the margin of error stays below a prespecified value \(m\) at a given confidence level.

Trade-off: Precision vs. Cost

As the sample size increases, the margin of error decreases, improving precision.

However, collecting more data comes with increased time, cost, and effort.

This is why planning ahead is crucial: we need a large enough sample size to achieve the desired margin of error \(m\), but not unnecessarily large to waste resources.

Starting with the Margin of Error Formula

To determine the required sample size, we begin with the formula for the margin of error, which depends on the confidence level and the variability in the population.

Note

1. Margin of Error for a Mean \(\mu\)

A one-sample t confidence interval has the margin of error:

where:

\(n\) is the sample size,

\(t^*\) is the t-critical value for the desired confidence level (depends on \(\text{df} = n - 1\)),

\(s\) is the sample standard deviation after collecting data, but we guess a value \(s_g\) beforehand when planning.

Goal: Choose \(n\) to achieve an expected margin of error \(\le m\).

Since we won’t know the actual \(s\) until we sample, we use our best guess \(s_g\) for calculations.

If previous studies or pilot data are available, we might estimate \(\sigma\) from those results.

In the absence of prior data, subject-matter expertise or known properties of the data can guide us.

A simple rule of thumb:

Justification: For many roughly bell-shaped distributions, the range spans about 4 standard deviations (from roughly \(\mu - 2\sigma\) to \(\mu + 2\sigma\)), so dividing the range by 4 provides a crude estimate of \(\sigma\).

Although not exact, it can be a useful starting point for sample-size or margin-of-error calculations when more precise estimates of \(\sigma\) are unavailable.

Note

2. Iterative Search Approach

Because \(t^*\) itself depends on \(n\), an iterative method is often used:

Initial Approximation:

Replace \(t^*\) with the corresponding z-value (as if \(\sigma\) were known).

Solve

\[ n = \Bigl(\frac{z^*\,s_g}{m}\Bigr)^2\]and round up to the nearest integer.

Refine Using t Distribution:

With the tentative \(n\), find the actual \(t^*\) for confidence level \(C\) and \(\text{df} = n-1\).

Check if \(m \ge t^* \cdot \frac{s_g}{\sqrt{n}}\).

If not met, increment \(n\) and repeat.

This process continues until the requirement \(m \ge t^*\frac{s_g}{\sqrt{n}}\) is satisfied.

Note

3. Two-Sample Case

To design for a two-sample t confidence interval for \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\):

Often assume equal sample sizes \(n_1 = n_2 = n\) and similar standard deviations \(s_1 \approx s_2\).

The margin of error for \(\bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}_2\) becomes

\[ m = t^* \cdot s_g \,\sqrt{\frac{1}{n} + \frac{1}{n}} \;=\; t^*\cdot s_g\sqrt{\frac{2}{n}}.\]We again guess \(s_g\) and use an iterative method (now with \(\text{df} \approx 2(n-1)\)) if we need a more precise approach.

In addition to planning for the sample size \(n\), we often also need to consider the power of our hypothesis test. These two concepts are closely related. Looking at the list of factors that influence power, we see that the first three also impact the margin of error.

Significance Level \(\alpha\)

A 5% test (\(\alpha=0.05\)) is more likely to reject \(H_0\) than a 1% test (\(\alpha=0.01\)) for the same true alternative, simply because less evidence is required to reject \(H_0\).

Population Standard Deviation \(\sigma\)

More variability (larger \(\sigma\)) makes it harder to detect a true difference from \(H_0\).

With less variability, the test statistic is more sensitive to departures from \(H_0\).

Sample Size \(n\)

Larger \(n\) reduces the standard error, making it easier to detect a given difference.

Power increases as \(n\) grows.

The Alternative (Effect Size)

The farther the true parameter is from the null hypothesis value, the easier it is to reject \(H_0\).

We often measure this distance as “effect size” = \(\frac{\text{departure from }H_0}{\sigma}\).

Before collecting data, researchers often choose:

\(\alpha\): The significance level (e.g., 5%).

Minimum Detectable Effect: The smallest departure from \(H_0\) that matters in practice.

Desired Power (e.g., 80% or 90%).

Estimate of \(\sigma\) (or \(\sigma\)s in two-sample scenarios).

Software is typically used to solve for the required sample size \(n\) that achieves the target power for detecting the specified effect size at level \(\alpha\).

Calculating Power

Reject \(H_0\) Region: Determine the critical test statistic(s) that lead to rejection, based on \(\alpha\).

Assume a Specific \(\mu\) (or Effect Size) Under \(H_a\): Find the probability that the test statistic falls in the rejection region, given this alternative is true.

Mathematically, this requires a noncentral t distribution (or other distribution, depending on the test). Manually this is tedious, so we rely on statistical software.

7.4. Unbiasedness and Consistency of the Sample Standard Deviation#

Let \(X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n\) be i.i.d. random variables with mean \(\mu\) and variance \(\sigma^2\).

Define the sample variance:

Key Result: \(\mathbb{E}[s^2] = \sigma^2\).

Here’s the sketch of the proof:

One can expand \((X_i - \bar{X})^2\) into \(\Bigl[(X_i - \mu) - (\bar{X} - \mu)\Bigr]^2\) and use the fact that

Taking expectations and using \(\mathbb{E}[(\bar{X} - \mu)^2] = \frac{\sigma^2}{n}\) yields

Hence,

Therefore, \(s^2\) is an unbiased estimator of \(\sigma^2\).

To show consistency, we want:

Consistency of \(s^2\)

By the Strong Law of Large Numbers,

\[\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \mu)^2 \;\to\; \sigma^2 \quad\text{almost surely.}\]Observe that

\[s^2 = \frac{n}{n-1} \cdot \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \bar{X})^2 \approx \frac{n}{n-1} \cdot \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \mu)^2,\]where the second step uses \(\bar{X} \approx \mu\) for large \(n\).

Since \(\frac{n}{n-1} \to 1\) and \(\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \mu)^2 \to \sigma^2\), it follows that \(s^2 \to \sigma^2\) in probability (or almost surely under mild conditions). Thus, \(s^2\) is a consistent estimator of \(\sigma^2\).

Consistency of \(s\)

By the Continuous Mapping Theorem, if \(s^2 \xrightarrow{\;p\;} \sigma^2\) and the square-root function \(\sqrt{\cdot}\) is continuous for \(\sigma^2>0\), then

\[s = \sqrt{s^2} \;\xrightarrow{\;p\;} \sqrt{\sigma^2} = \sigma.\]Hence, \(s\) is a consistent estimator of \(\sigma\).